This section provides regularly updated content about my ongoing practice-based PhD research at the Edinburgh College of Art.

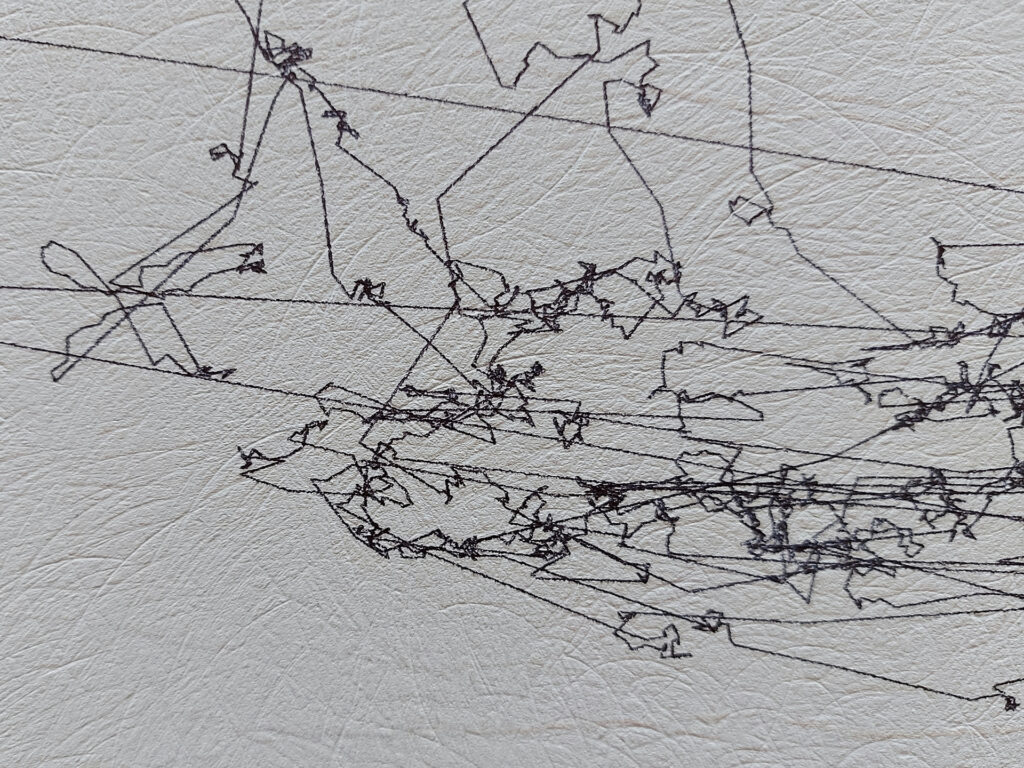

My research explores possible uses of an eye-tracking device as a drawing medium, and I primarily focus on drawing with my eyes with the eye tracker.

This research is funded by the Malta Arts Scholarship scheme.

A paper about the eye-tracking drawing project Id-Dgħajjes tal-Fidili, published by the drawing journal Drawing: Research, Theory, Practice is now available at the following:

Attard, Matthew (2022), ‘Eye (re)drawing historical ship graffiti: Tracing ex-voto drawings with eye-tracking technology’, Drawing: Research, Theory, Practice, 7:2, pp. 185–98, https://doi.org/10.1386/drtp_00088_1

28: Ħars fuq ħars

Ħars fuq ħars is a six-artist visual experiment taking place within the project space at Valletta Contemporary, in parallel with the solo exhibition rajt ma rajtx… naf li rajt and curated by Margerita Pulè. The contributing artists are: Gilbert Calleja, Charlie Cauchi, Ryan Falzon, Charlene Galea, Roxman Gatt, Alexandra Pace.

The video below features some installation views from the project.

curated by Margerita Pulè

Contributing artists:

Gilbert Calleja

Charlie Cauchi

Ryan Falzon

Charlene Galea

Roxman Gatt

Alexandra Pace

A six-artist visual experiment, in parallel with the solo exhibition rajt ma rajtx… naf li rajt.

25 Sept – 15 Nov 2021 at Valletta Contemporary

Matthew Attard is a current PhD candidate at the Edinburgh College of Arts, University of Edinburgh, funded by the Malta Arts Scholarship Scheme – The Ministry for Education and Employment.

The exhibition is also supported by Doneo Ltd.

Most of the past six months have been dedicated to the production of the solo show rajt ma rajtx… naf li rajt, curated by Elyse Tonna at Valletta Contemporary, which also features supporting works by invited artists reinforcing multiple points of view. These include: Caesar Attard, Nanni Balestrini, Aaron Bezzina, Matyou Galea, Francesco Jodice and Pierre Portelli. The video below is a walk-through of the exhibition.

I/you saw, but I/you did not see… I know that I/you saw

Matthew Attard

curated by Elyse Tonna

with supporting works by Caesar Attard, Nanni Balestrini, Aaron Bezzina, Matyou Galea, Francesco Jodice and Pierre Portelli.

25 Sept – 15 Nov 2021 at Valletta Contemporary

Matthew Attard is a current PhD candidate at the Edinburgh College of Arts, University of Edinburgh, funded by the Malta Arts Scholarship Scheme – The Ministry for Education and Employment.

The exhibition is also supported by Doneo Ltd.

26: Doodling with the eyes

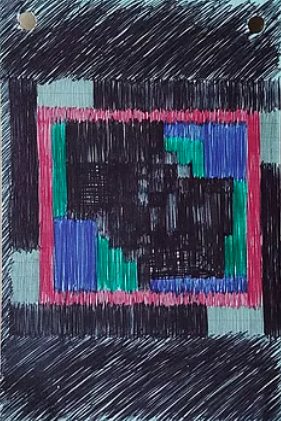

This eye drawing experiment consists in doodling with the eye-tracker while also mark-making on paper.

I wore the monocular eye-tracker while doodling the drawing below on a squared green paper. A multi-coloured BIC pen was used and there was no pre-planning of what to draw/doodle. I intuitively found myself elaborating the doodle through the squares presented by the surface. The doodle happened on different days, which prompted the use of different colours. Before each doodling session, the Pupil Core monocular eye-tracker was calibrated and recording started contemporarily to the doodling. During the post-processing of the data, the resulting eye-drawings were colour-coded in correspondence to the doodle.

Figure 54: The images above read from top-left to bottom: Hand drawn mark-making doodle made using a BIC coloured pen and pencil on green squared paper 10 x 15 cm; a rotating loop representation of the resulting eye-doodle in the virtual space; a second rotating loop representation of the resulting eye-doodle in the virtual space; and a still image of the eye-doodle.

25: Eye drawing my room

During the 2020 lockdown, my room became my studio and it is where most of the eye drawing practice took place.

Towards the end of summer I edited some selected eye-drawings of features such as my desk, my hand and the view from my window among others into a rotating spatial eye-drawing.

Figure 53: Top Still image of a spatial eye-drawing of my room.

Bottom A rotating loop of a spatial eye-drawing of my room.

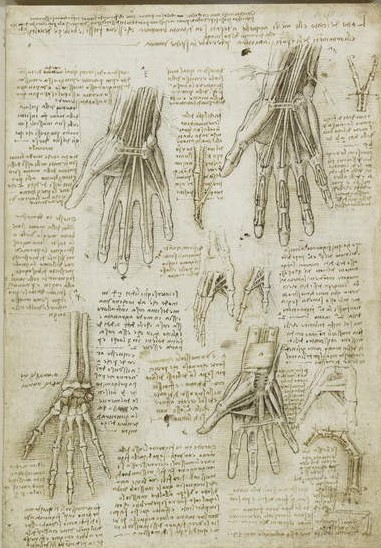

The decision to eye draw from da Vinci’s anatomical drawn notations about the bones of the hand was a different one from that of drawing Géricault’s. These hand drawings involve anatomical observation and notation Figure 52, where the underlying structure of a hand’s anatomy is drawn with engineer-like precision. The drawing itself seems to have been built in stages, starting from the bones and working up towards the sets of muscles and tendons. While eye drawing from these drawings, I attempted to follow and perceive this same build-up through my gazing. My intention was not to get an anatomical precision of da Vinci’s illustration of the hands, but to follow his linear drawn elements with my eyes.

Figure 50: One of the eye-drawings resulting from eye drawing Figure 52 at a distance of 50cm from the computer screen using the binocular eye tracker.

Figure 51: One of the eye-drawings resulting from eye drawing Figure 52 at a distance of 50cm from the computer screen using the binocular eye tracker.

Figure 52: Da Vinci’s notes and drawings about the bones of the hand, c.1510-11, black chalk, pen and ink, wash on paper, 28.8 x 20.2cm, Royal Collection Trust.

23: Géricault’s ‘Left hand’

Many artists throughout history have drawn their hand for a variety of reasons. In her section dealing with anatomical body parts, Petherbridge (2010; 251-259) mentions how, symbolically, hands can allude to the individuality of the artist. In view of this she discusses Géricault’s drawing of his left hand, drawn in watercolours on his deathbed. He started by extending his arm onto paper, and traced along it, of which markings are still visible at the fingertips (Figure 49). This trace was the starting point for the drawing, from which he then built-up the image of his hand. Apart from the captivating story behind this drawing, now at the Louvre in Paris, Géricault’s very act of extending his arm and tracing it made me want to attempt to eye draw it (Figure 47 & 48). He might have started his drawing from a traced-outline due to his bedridden state, but at the same time, the gesture of extending one’s arm and drawing the hand is a gesture that shouts; “I am here, this is what I see and this is how I see it”. I wanted to eye draw it with the aim of recontextualising (and re-draw) this presence through my gaze.

__________

References:

Petherbridge, D. 2010. The primacy of drawing : Histories and theories of practice. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Figure 47: One of the eye-drawings resulting from eye drawing Figure 49 at a distance of 50cm from the computer screen using the binocular eye tracker.

Figure 48: One of the eye-drawings resulting from eye drawing Figure 49 at a distance of 50cm from the computer screen using the binocular eye tracker.

Figure 49: Théodore Géricault, La main gauche de Géricault, 1823, watercolour on paper, 22.5 x 29.5cm, Louvre collection, Paris.

The experiments below consisted in eye drawing an aloe plant from a distance of about 45 cm by contouring/delineating the boundaries of the 3-dimensionality of my hand, using the Pupil Core binocular eye tracker and the Fingertip calibration method.

Figure 45: Eye-drawing of an aloe plant and pot

Figure 46: Eye-drawing of an aloe plant and pot

The experiment below consisted in eye drawing my right hand at a distance of about 45 cm and its reflection in the mirror by contouring/delineating the boundaries of the 3-dimensionality of my hand, using the Pupil Core binocular eye tracker and the Fingertip calibration method. 7517 points were recorded in 40 seconds.

Figure 44: Eye-drawing of my right hand and its reflection in a mirror

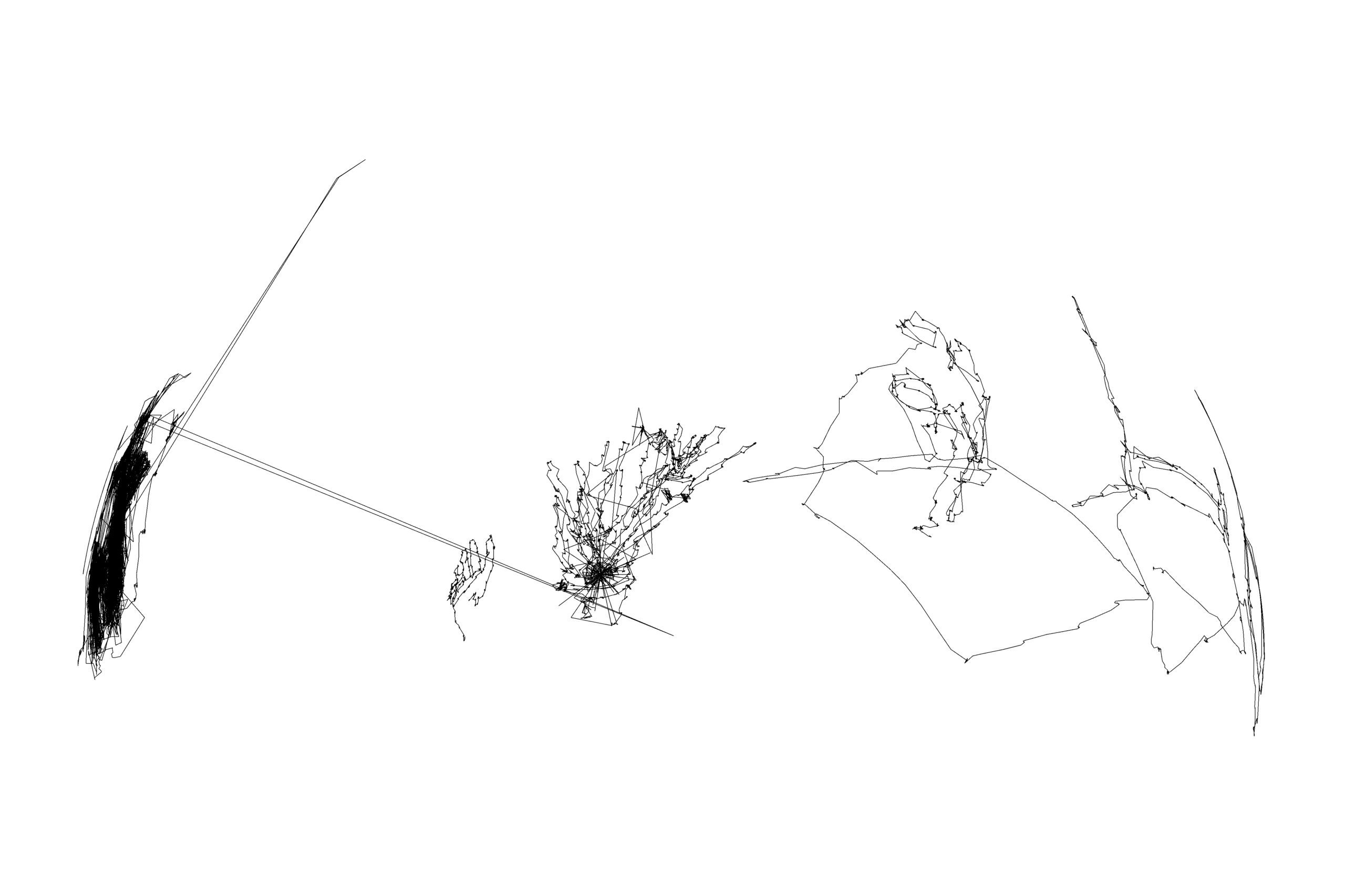

The experiment below consisted in eye drawing my right hand from different viewpoints by contouring/delineating the boundaries of the 3-dimensionality of my hand, using the Pupil Core binocular eye tracker as a result of the Screen Marker calibration. 9383 points were recorded in 51 seconds.

Figure 43: Eye-drawing of my right hand from different viewpoints