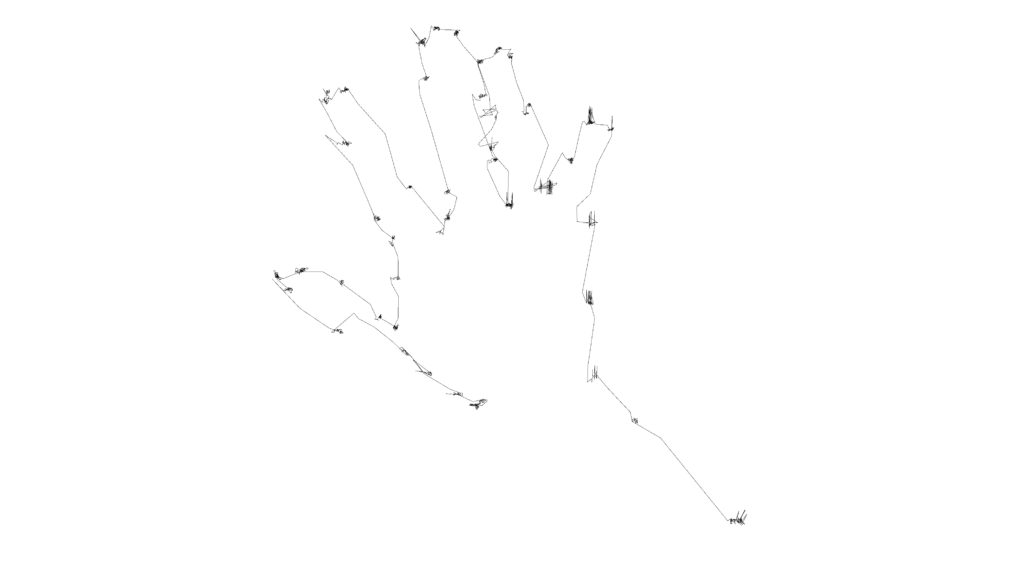

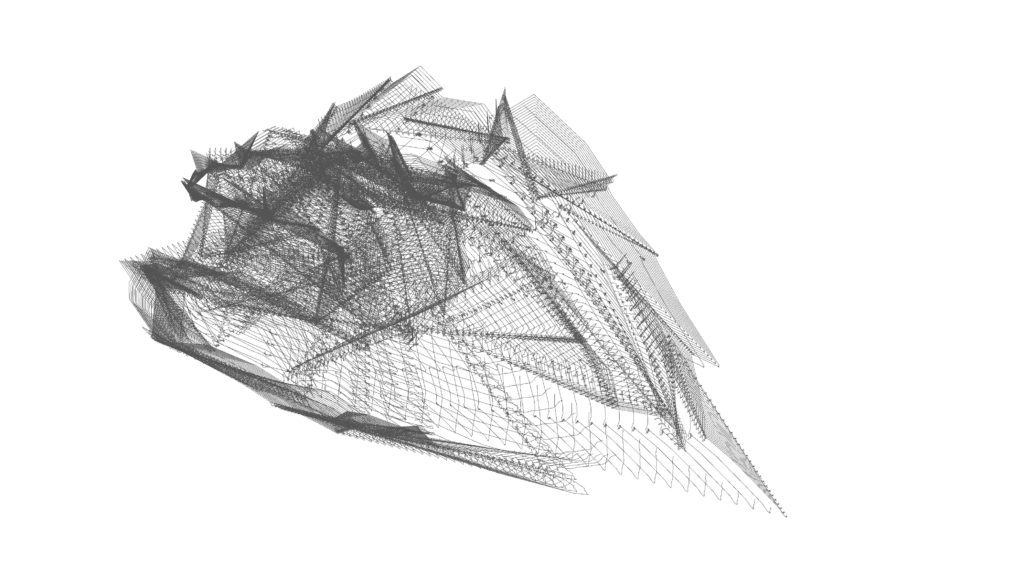

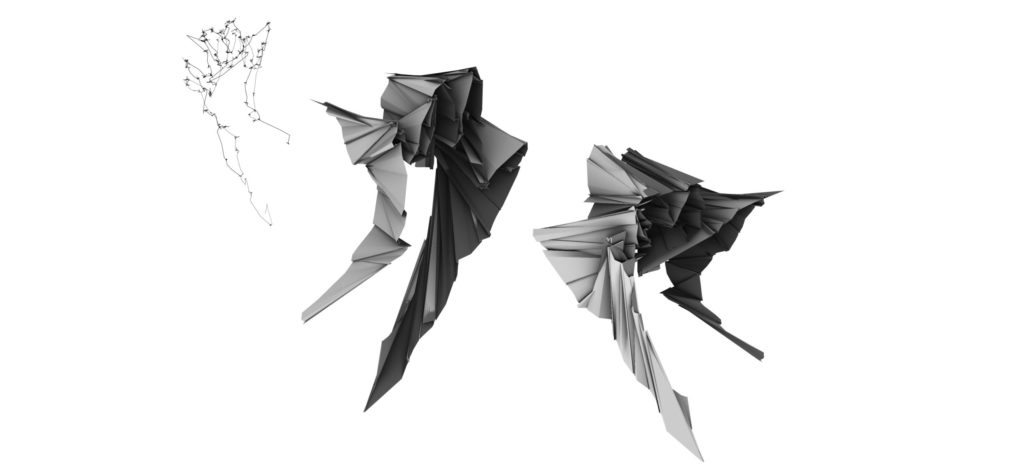

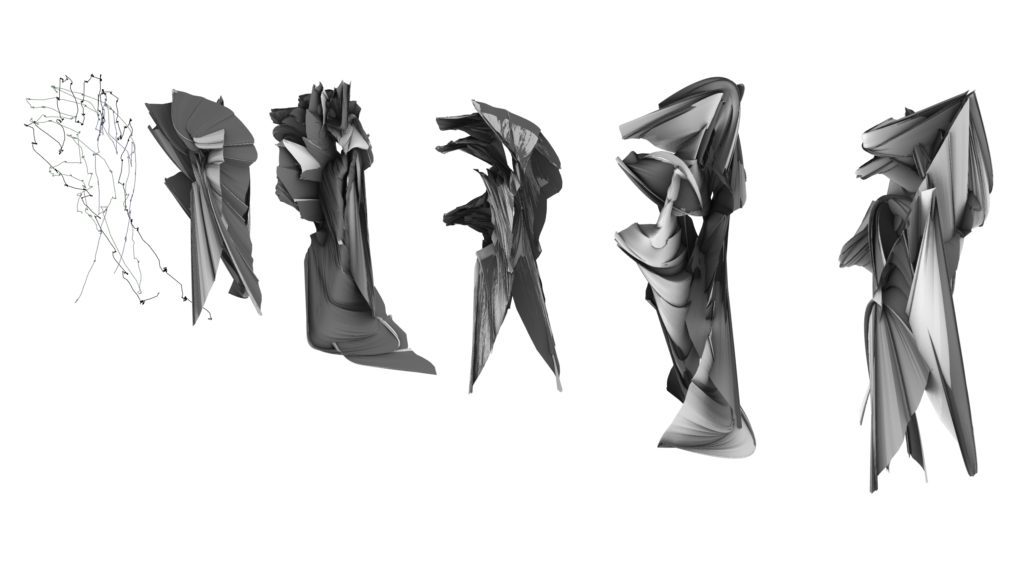

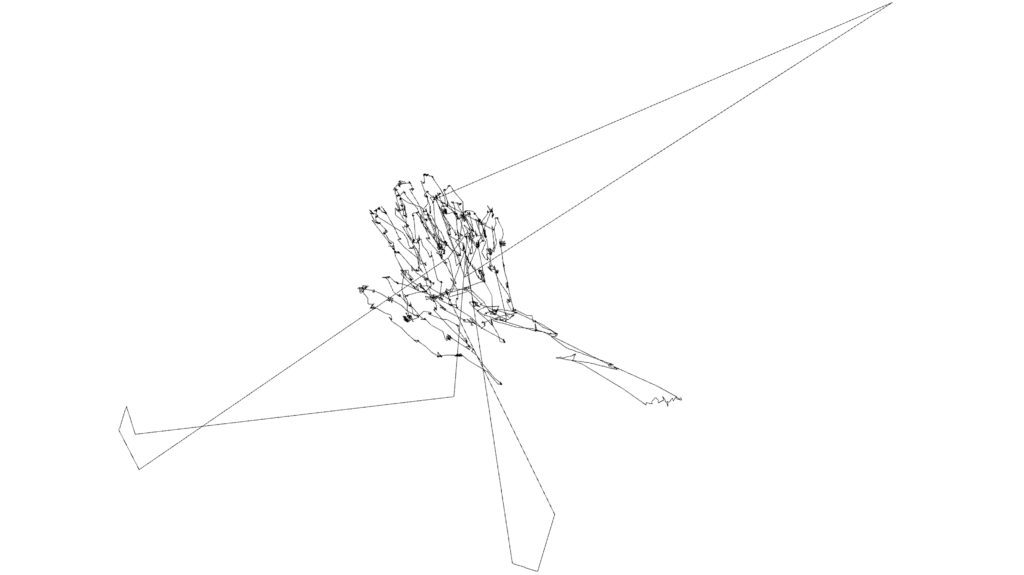

Figure 30: Eye drawing my own hand

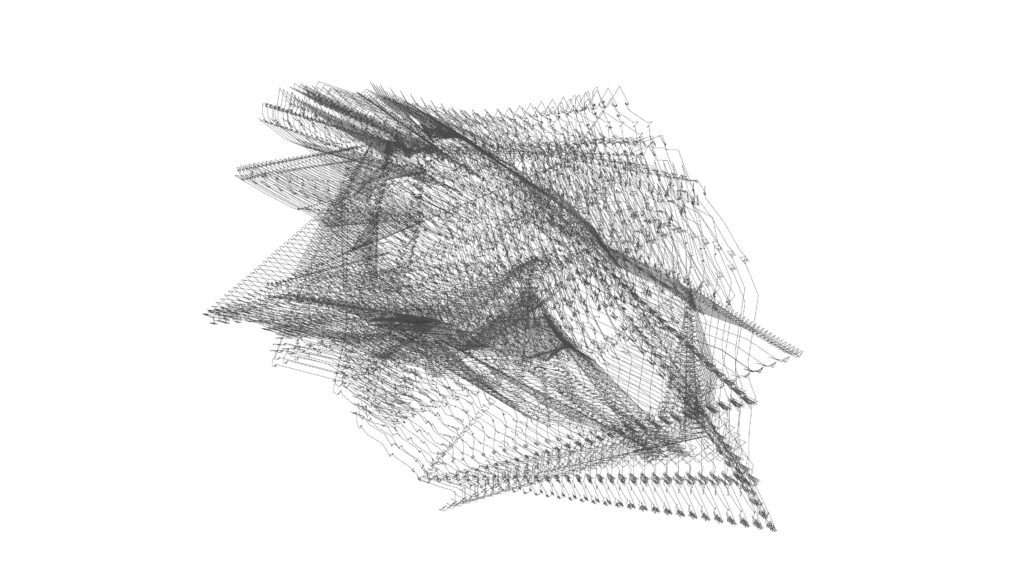

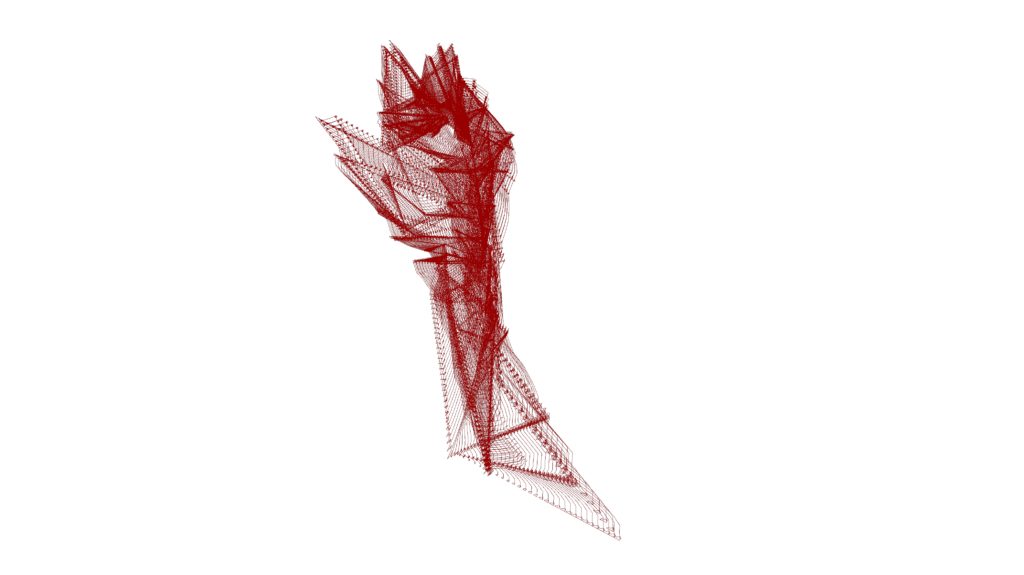

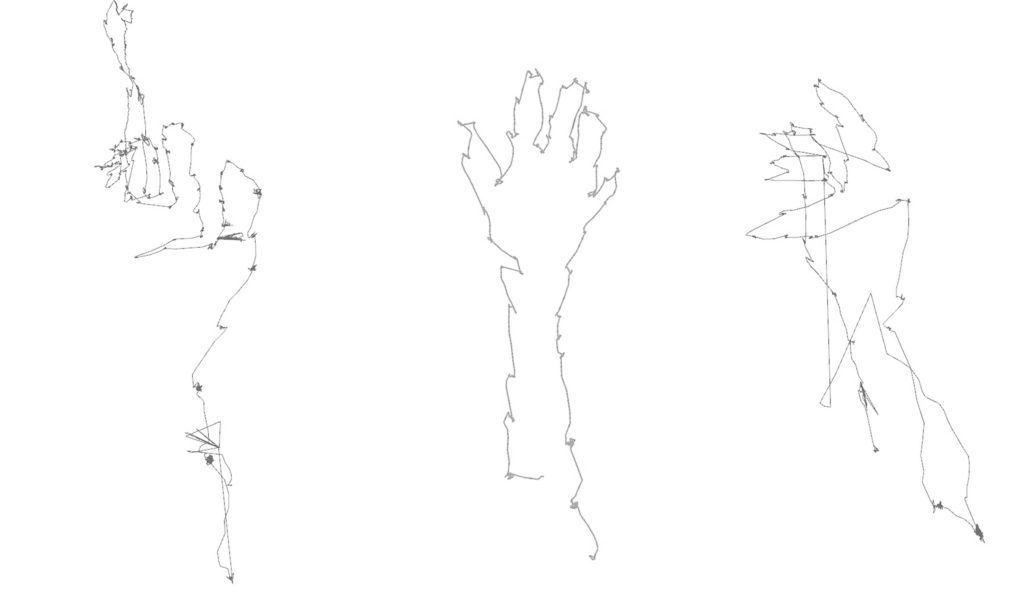

Figure 31: Resulting eye-drawing from Figure 30

Within my practice of eye drawing, the tangible surface is not present,

and therefore the act of drawing navigates between the eye and the mind. This enhances my visual perceptive mechanism, as the gazing point on the subject (my hand) is a conceptually imagined point. I have no physical reference of where the point is while eye drawing, and technically speaking I would be lost if not for our inner perceptive mechanisms such as imagination and memory. The latter are mental functions which are of a volatile and flexible nature, and therefore this also means that its limitations characterise each eye-drawing. This point reminds me of the question that if drawing is merely about the eye-hand coordination, what difference is there with a game of tennis? (Walker 2005). I feel that the correspondence with our interior mental image while drawing is this crucial difference.

Figure 31 explicitly illustrates the tension provided by the restraining of my body movements — and specifically, the controlling of the eye movements. Occurrences of evident inattention can be observed. These make-up for the aesthetic compositional arrangement of the eye-drawing, which is characterised by occasional spikes away from the concentration of the hand. I find this information to be of utmost interest within this practice. Firstly, I am not aware these movements happened while eye drawing my hand — I only discovered them at a later stage during post-processing. Therefore, I see them as being part of our innate biological aspects which escape the attempt of restraining my eye movements into a different way of looking from our natural perceptive functioning.

__________

References:

Walker, J. (2005). Old Manuals and New Pencils. in Davies, J., & Duff, L. (eds.). Drawing, the process. Bristol, UK: Intellect.